In my previous post I spoke about owning your own content and controlling how it’s published. This post is something that demonstrates the value of having your content online. I’ve never written about this before, I don’t know why, it was very interesting to be part of.

At the start of 2010 I gave a presentation at VALA titled Everything I know about cataloguing I learned from watching James Bond (PDF). The presentation explored using facial recognition (using a sample set of photos of our Prime Ministers) and colour analysis as different ways to match and explore items within a collection. At the time it was pretty advanced, now, 8 years since the research took place, some of it seems pretty primitive as there’s been massive advances particularly in facial recognition and other forms of computer vision and artificial intelligence.

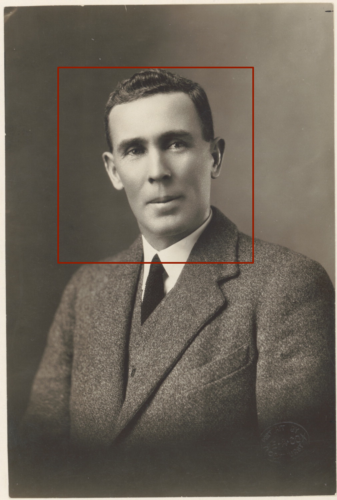

About 18 months after the presentation I had a phone call at work from the journalist Ross Coulthart. He had come across my paper from VALA and had an interesting opportunity on offer. Kerry Stokes AC had just purchased the Thuillier photographic collection of World War One soldiers that was discovered in a French farmhouse attic (now more commonly known as the lost diggers of Vignacourt). This collection consisted of over 3000 glass plate negatives of Australian, British, American, Canadian and other allied soldiers from the First World War.

Ross got in touch, because, they had these beautiful images, but there was no record of who the soldiers were in the pictures. They had built a website to try & crowd source details, but he thought there had to be a better way. Having come across my paper & seeing as I worked at the library, he wanted to see if we could use the techniques I had experimented with to possibly match these images to any images from our collections that might have names associated with the image. Of course, I jumped at the opportunity!

Being at the library, it was the perfect place, as I had access to Trove so it wasn’t just the National Library’s photo collection, it was essentially an Australian collection of photos. To extract a selection of images I looked at images with dates from 1910-1929 taking the dates wider than just the First World War as many images were taken prior to the war starting or from their return. This sample was then refined by extracting images with titles or descriptions that matched a list of military ranks:

- general

- brigadier

- colonel

- major

- captain

- lieutenant

- cadet

- sergeant

- warrant officer

- corporal

- private

- signalman

- gunner

- trooper

- sapper

- recruit

- portrait

- cpl

- digger

Images were then run through a simple face detection algorithm to generate some level of accuracy indicator. This basically just returned the number of faces detected in an image. Many of the images were group portraits of units (so lots of faces detected). Getting great facial details was going to be much harder to detect compared to a head and shoulders portrait (where only 1 face would be detected). This also had the added bonus of eliminating false positive landscape photos that contained terms like “general view of…” in the title. In addition to military groups, it also brought back a lot of sporting group photos (as they listed the captain of the team in the description). I grouped these into portraits, groups (military) and groups (sporting).

I then used this dataset to crawl the relevant institutions sites and download the highest resolution image that was available online (in many cases just a 450 or 600 pixel wide/tall image). Due to time constraints it would have been impractical to attempt to order high resolution scans of all the images.

This resulting dataset, contained just over 5,100 images.

At this stage, my contribution was done. Once I passed these images & data on to Seven, they used facial recognition services (from I believe a security firm) to compare and match these images to the glass plate negatives. Unfortunately, this process didn’t match any of the unknown soldiers with known soldiers. From what I can recall there were issues at the time with just using screen resolution images, with many of the images lacking the required detail for matching.

Despite not getting an outcome, it was a fascinating process to go through & was a really nice outcome that validated what I set out to do when undertaking the research for my paper.

It’s been so exciting to see what happened since I made my little contribution to the project, it went on to great things: there was a feature on the Sunday Night TV show, a book, an exhibition and permanent home for the collection at the Australian War Memorial.

Now, 6 years on from when the initial work was done, if it was done again it might provide different results. Facial recognition software has improved so much. Many institutions are also delivering much higher resolution images on their sites than they were back then.A combination of just these 2 items might prove to be more successful for other projects embarking on trying to solve a similar problem. If I was to undertake the same problem today, I would probably just load a data set into my phone & let the photos app analyse everything. I could simply do a search for “soldier”.

The moral of the story, put your ideas and thoughts online. You never know who will discover them and what they might lead to.

Comments

One response to “Lost diggers”

I love this message. I’ve been thinking about what open access might mean in terms of techniques, processes and skills in my workplace, and how to break down cultural silos. I think this idea needs to merge with Sly July to talk about cross fertilisation of ideas. Will think more. Enjoying your return to your site very much, thanks for posting!